But the rock that Abiyoyo obligingly flings aside smashes the wand. Call on Abiyoyo, suggests the granddaughter of the man with the magic wand, then just “Zoop Zoop” him away again. Faced with yearly floods and droughts since they’ve cut down all their trees, the townsfolk decide to build a dam-but the project is stymied by a boulder that is too huge to move. The seemingly ageless Seeger brings back his renowned giant for another go in a tuneful tale that, like the art, is a bit sketchy, but chockful of worthy messages. Do you know how talented you are?” Polacco’s disdain for all the other teachers and the students intrudes on Trisha’s more profoundly heartbreaking perspective the book lacks the author’s usual flair for making personal stories universal. Falker, watching her draw, whispers, “This is brilliant.

Or the best at anything”-is contradicted when Trisha is the object of praise: Mr. Falker’s implicit sense of fairness-“Right from the start, it didn’t seem to matter to Mr. Falker (complete with a classroom version of a “He who is without sin among you” scene) is mawkish. Falker and Miss Plessy had tears in their eyes.” The extent to which Trisha limns her own misery and deifies Mr. Although the perspective is supposed to be Trisha’s, many sentences give away the adult viewpoint, e.g., “She didn’t notice that Mr. A thank-you to a teacher who made a difference is always welcome, but this one is unbearably sentimental. Falker silences the children who taunt Trisha, and begins, with a reading teacher, to help her after school. She can draw well, but is desperately frustrated by math and reading.

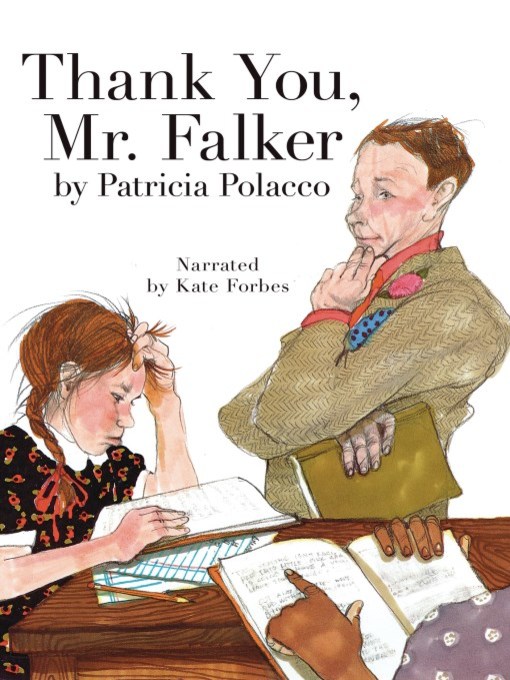

Trisha begins kindergarten with high hopes, but as the years go by she becomes convinced she is dumb. An autobiographical tribute to Polacco’s fifth-grade teacher, the first adult to recognize her learning disability and to help her learn to read.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)